First, a reminder of two fall worskhops:

Grief Writing Workshop: Sundays, September 7, 14, 21, 28, October 5, 12. In this workshop, we will explore filmmaker Kirsten Johnson’s notion that it is never too late to get to know someone you love more deeply, even after they are gone. We will explore our losses and our lost loved ones through creative writing, with the hope (and the belief) that this communal work will be of use to all of us as we move through our grief process(es). The course is appropriate for those who already have projects underway as well as for those who don't, and for those who might just be curious to see what writing can do for them; we will generate new work as well as share with one another. More details here, message me with any questions.

Creative Prose Workshop: Sundays, 10/26, 11/2, 9, 16, 23. This workshop is for any person with a prose writing project that could use some readers. We will meet online for five weeks, with five sessions of 1.5 hours each. Open to all, no matter the project or level of experience. More details here, message me with any questions.

I will also be offering private writing coaching on a limited basis. Please get in touch (info@nelliehermann.com) with details about your situation and desires!

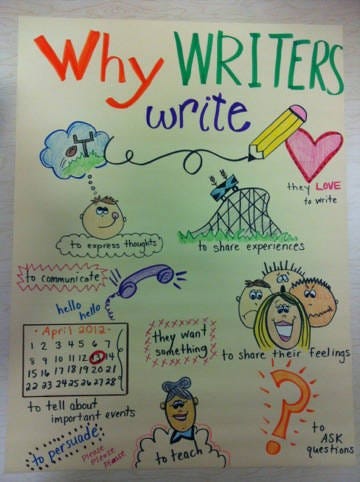

The question of why we write is an eternal one. Countless writers have tackled the question; anthologies have been published; Yale University Press has a book series where writers meditate on it. It is a question that endlessly fascinates and motivates me — I love that we keep asking it, keep answering it in different ways. When working with healthcare providers—who are not trying, necessarily, to publish, or to turn writing into a profession—the question feels even deeper, more close to its source. What does writing do for us in the most fundamental of ways; why do we write as a species? What possibilities lie out there in writing, in the practice of the use of language to express ourselves? What can writing do for us away or aside from capitalist concerns?

One side of the question of course is a differently-worded and more barbed question: what is the point? Again, this question has many contexts and is asked with varying amounts of edge — in healthcare it has a particular sharpness to it (“why do doctors need to know how to write?” is a question I’ve heard countless times), a confusion that can be used to justify cuts in funding or turns toward AI. “The point,” when it comes to writing, is not something quantifiable (an important word for healthcare)…which is a whole other topic for another day.

But this “what is the point” question is a ghost that haunts even those of us who are already fully committed to the work of writing. Again, writers have answered and pushed back against the question in countless ways. Audre Lorde’s “Poetry is not a Luxury” (read it if you have not yet), one of the most powerful pushbacks there is, starts like this:

The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are, until the poem, nameless and formless-about to be birthed, but already felt.

“The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives” — there is a beautiful answer.

But the question doesn’t easily go away, especially in times of terror and stress, like the one we are in now. In a recent session with the USAID cohort, we read Dunya Mikhail’s “My Poem Will Not Save You,” a poem that speaks directly to this question. Here are the last two stanzas of the poem (sorry to cut it, please click above to read the whole thing):

My poem cannot return all of your losses, not even some of them, and those who went far away my poem won’t know how to bring them back to their lovers. I am sorry. I don’t know why the birds sing during their crossings over our ruins. Their songs will not save us, although, in the chilliest times, they keep us warm, and when we need to touch the soul to know it’s not dead their songs give us that touch.

Again, here’s an answer — “when we need to touch the soul/to know it’s not dead/their songs” — our poetry, our language — “give us that touch.”

In the session, we spoke about the feeling of uselessness, the frustration around speaking up—why bother, why write? If we can’t stop these terrible things from happening, if our contribution is so small, why do we do it, and/or how do we wrestle with the internal voices that tell us it’s all useless, there is no point?

We spoke about this even as we also said that we didn’t really believe it was useless; of course we didn’t, because there we were, gathered to write together. We can acknowledge it and also move forward, we can say yes my voice is small and I have only one and I’m not going to prevent anything from happening but also I can still show up and write something nonetheless. Because I am alive and I protest. Because we are human and we have souls and there is pain. Because one voice raised joins another voice raised and soon there is a chorus that can be heard.

Just as I was beginning to write this post, Alexander Chee published a post on his substack examining the question of how to write “at a time like this” (again, go read!):

It feels like a storm of horror just to read the news and I know it is on purpose. Bad news without a way to react or meaningfully help out spreads psychic numbing and despair. And yet to not know the news is to live helplessly. But my despair and yours, they are worth everything to Trump and so what can I do but disappoint him, to spite him. He needs our despairs and so I do not give mine, as this refusal, like my writing, is at least in my control. I hope you will do the same.

In this spirit I will share three pieces that came from that same session, inspired by “My Poem Will Not Save You.” I left that session feeling so reassured, in terms of this ghost that haunts us, this question of why, this elusive point. The doing of the work — the reading, the writing, the sharing, and for me, the witnessing of each of these people putting words down and then sharing their vulnerability — this is why. We are expressing something and we are listening to one another. The language is connecting us. Do we need more “why” than this?

First, by Jessica Zaman:

My poem will not save you

Words can be employed to speak your pain

Their black images splashed across a weathered page

Words can speak the horrors you’ve witnessed

And plaintively ask why your loved one was taken so

They can describe the desperation as you wait like cattle for a box of food

The lack of water, clean or otherwise, and the truth of the world turning away, ever new conflicts flashing across screens

My poem cannot change the indignities and the heartbreak

My only power is to document the destruction, the pain and the chaos

**

Second, by a participant who wishes to stay anonymous:

I am sorry my words won't make any difference.

I want to write a brilliant letter or essay or article to those in my extended family, to friends, to the church, to say,

"These numbers of children who will die are real. Millions of people were saved by the quiet administration of immunizations and specially-engineered food, and by giving blood to the dying."

I want to write clever and compelling words that ask,

"How can you believe the lies, the"narrative"?"

My words will point me out as a leftist, a radical, an "unbeliever," some will say.

But I will, I must, listen to the birds sing. And I must, I will try, to write.

Even if my words will not save us.

**

And lastly this third one (also by a person who wants to stay anonymous), written in a very different vein, which I love:

Does everyone have a soul?

The people who did this— who walked, glassy-eyed, forward, leaving behind destruction. Setting off memo bombs, whose mushroom clouds extend now, lawless, consuming children who need food, need medicine, need the touch of a soul who cares. Is nothing there, curled up in their chests? A soul, origamied into a tiny crush of paper. Is there no way to unfold it, to make it hear the cries?

To this last question, I don’t know. It seems real hard if not impossible, these days, to unfold those orgamied souls, if indeed they are even there. But, as Dunya Mikhail wrote, this work is for touching the soul to know it is not dead. And we are trying, and we will keep trying as long as we can.